This document describes the syntax and semantics for the chunk graph and rules format. A formal specification is in preparation for publication as a Community Group Report.

- Introduction

- Sandbox for learning Chunks and Rules

- Formal specification

- Mapping names to RDF

- Chunk Rules

- Statements about statements

- Tasks

- Ebbinghaus forgetting curve

- Test Suite

- Boosting performance

- Relationship to other rule languages

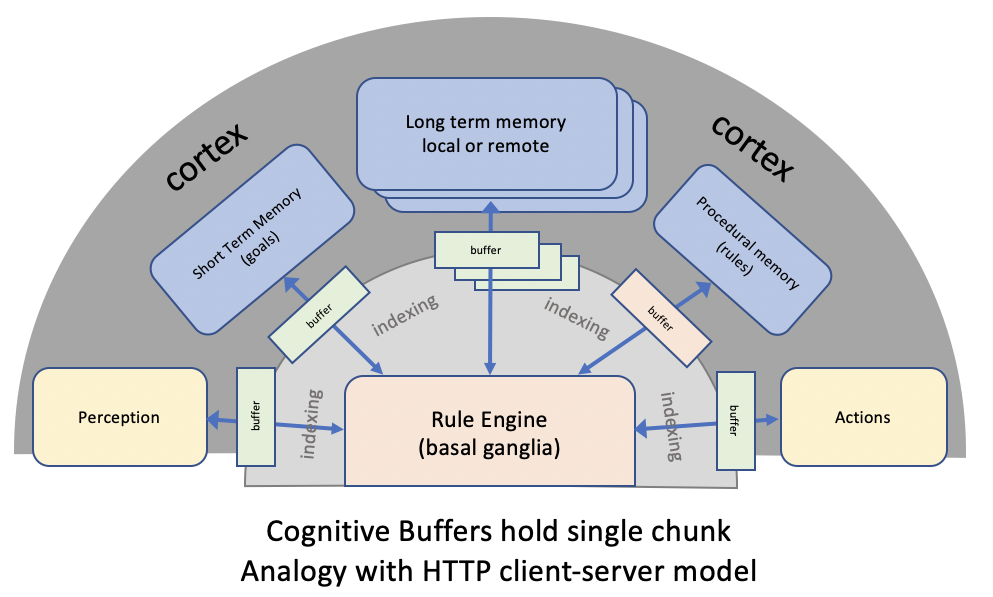

The chunks and rules format is designed for use in mimicking the cortico-basal ganglia circuit, which functions as a sequential rule engine:

The cortex consists of a set of modules that hold collections of chunks and are accessed via buffers. Each buffer holds a single chunk and represents the current state of a bundle of nerve fibres connecting to a particular cortical region. The rule engine matches rule conditions to the current state of the buffers, and the rule actions can either directly update the buffers or invoke module operations that indirectly update the buffers. The module buffers can be likened to HTTP clients while the cortical modules can be likened to HTTP servers. This architecture originates in John Anderson's work on ACT-R.

Each chunk is a named typed collection of properties, whose values are names (e.g. for other chunks), numbers, booleans (true or false), ISO8601 dates, string literals or comma separated lists thereof. This can be contrasted with a minimal approach in which property values are restricted to names.

Here is an example of a chunk where each property is given on a separate line:

dog dog1 {

name "fido"

age 4

}

Which describes a dog named fido that is 4 years old. The chunk name, (i.e. its ID) is dog1. This uniquely identifies this chunk within the graph it is defined in. You can also use the following syntax with semicolon as punctuation instead of newline e.g.:

dog dog1 {name "fido"; age 4}

The chunk ID is optional, and if missing, will be automatically assigned when adding the chunk to a graph. If the graph already has a chunk with the same ID, it will be replaced by this one. You are free to use whitespace as you please, modulo the need for punctuation. String literals apart from URIs must be enclosed in double quote marks.

The notion of type is a loose one and provides a way to name a collection of chunks that have something in common. It may be the case that all such chunks must satisfy some ontological constraint, on the other hand, it could be an informal grouping. This corresponds to the distinction between an intensional definition and an extensional definition. Inductive reasoning provides a way to learn models that describe regularities across members of groups.

Names are used for chunk types, chunk IDs, chunk property names and for chunk property values. Names can include the following character classes: letters, digits, period, and hyphen. Names starting with @ are reserved. A special case is the name formed by a single asterisk which is used to match any chunk type.

Numbers are the same as for JSON, i.e. integers or floating point numbers. Dates can be given using a common subset of ISO8601 and are treated as identifiers for read-only chunks of type iso8601 with properties for the year, month, day etc., e.g.

# Albert Einstein's birth date

iso8601 1879-03-14 {

year 1879

month 3

day 14

}

which also illustrates the use of single line comments that start with a #.

A similar approach is under consideration for numerical values with units of measure, e.g. 1.2cm and 9v which would map respectively to measure 1.2cm {value 1.2; units cm} and measure 9v {value 9; units v}.

Sometimes you just want to indicate that a named relationship applies between two concepts. This can expressed conveniently as follows:

John likes Mary

which is interpreted as the following chunk:

likes {

@subject John

@object Mary

}

Chunk properties can be promoted to relationships as in the following example:

# chunk for a sports player

Player p413 {

name "Lionel Messi"

dob 1987-06-24

# PlaysFor t87

}

# chunk for a relationship

PlaysFor r45 {

@subject p413

@object t87

since 2001-02

contract 2021

}

where property PlaysFor has been promoted to a relationship in order to annotate it with properties of its own. More generally, this design pattern can be used whenever you want to have properties that apply to other properties.

You can experiment with chunks and rules in your web browser, with the means to single step rule execution, to explore several tutorials and to edit the initial goal, facts and rules, and to save them across browser sessions.

This page provides an informal introduction. We're also working on a formal specification with a view to publishing it as a Community Group report.

The specification is at early stages of development. Feedback is welcome through GitHub issues or on the [email protected] mailing-list (with public archives).

To relate names used in chunks to RDF, you should use @rdfmap. For instance:

@rdfmap {

dog http://example.com/ns/dog

cat http://example.com/ns/cat

}

You can use @base to set a default URI for names that are not explicitly declared in an @rdfmap

@rdfmap {

@base http://example.org/ns/

dog http://example.com/ns/dog

cat http://example.com/ns/cat

}

which will map mouse to http://example.org/ns/mouse.

You can likewise use @prefix for defining URI prefixes, e.g.

@prefix p1 {

ex: http://example.com/ns/

}

@rdfmap {

@prefix p1

dog ex:dog

cat ex:cat

}

Sometimes it will be more convenient to refer to an external collection of mappings rather than inlining them, e.g.

@rdfmap {

@from http://example.org/mappings

}

where @from is used with a URI for a file that contains @rdfmap and @prefix declarations.

If there are multiple conflicting definitions, the most recent will override earlier ones.

Note: people familiar with JSON-LD would probably suggest using @context instead of @rdfmap, however, that would be confusing given that the term @context is needed in respect to reasoning in multiple contexts and modelling the theory of mind.

RDF is based upon a formal theory which relates expressions to interpretations. In particular:

A model-theoretic semantics for a language assumes that the language refers to a 'world', and describes the minimal conditions that a world must satisfy in order to assign an appropriate meaning for every expression in the language. A particular world is called an interpretation, so that model theory might be better called 'interpretation theory'. The idea is to provide an abstract, mathematical account of the properties that any such interpretation must have, making as few assumptions as possible about its actual nature or intrinsic structure. Model theory tries to be metaphysically and ontologically neutral. It is typically couched in the language of set theory simply because that is the normal language of mathematics - for example, this semantics assumes that names denote things in a set called the 'universe' - but the use of set-theoretic language here is not supposed to imply that the things in the universe are set-theoretic in nature. The chief utility of such a semantic theory is not to suggest any particular processing model, or to provide any deep analysis of the nature of the things being described by the language (in our case, the nature of resources), but rather to provide a technical tool to analyze the semantic properties of proposed operations on the language; in particular, to provide a way to determine when they preserve meaning. Model theory is usually most relevant to implementation via the notion of entailment, described later, and by making it possible to define valid inference rules.

For more details see the RDF 1.1 Semantics.

Formal semantics seeks to understand meaning by constructing precise mathematical models that can determine which statements are true or false in respect to the assumptions and inference rules given in any particular example. The Web Ontology Language (OWL) is formalised in terms of description logic, which is midway between propositional logic and first order logic in its expressive power. OWL can be used to describe a domain in terms of classes, individuals and properties, along with formal entailment, and well understood complexity and decidability. See, e.g. Ian Horrock's Description Logic: A Formal Foundation for Ontology Languages and Tools.

Chunks, by contrast, makes no claims to formal semantics, reflecting the lack of certainty, incomplete knowledge and inconsistencies found in many everyday situations. Instead of logical entailment, the facts are updated by rules in ways that have practical value for specific tasks, e.g. turning the heating on when a room is observed to be too cold, or directing a robot to pick up an empty bottle, fill it, cap it and place it into a box. Rules are designed or learnt to carry out tasks on the basis of what is found to be effective in practice.

- Web based sandbox for editing and single stepping through rules, using local storage for persistence

Applications can utilise a low level graph API or a high level rule language. The chunk rule language can be used to access and manipulate chunks held in one or more cognitive modules, where each module has a chunk graph and a chunk buffer that holds a single chunk. These modules are equivalent to different regions in the cerebral cortex, where the buffer corresponds to the bundle of nerve fibres connecting to that region. The concurrent firing pattern across these fibres encodes the chunk as a semantic pointer in a noisy space with a high number of dimensions.

Each rule has one or more conditions and one or more actions. These are all formed from chunks. Each condition specifies which module it matched against, and likewise each rule action specifies which module it effects. The rule actions can either directly update the module buffers, or they can invoke asynchonous operations exposed by the module. These may in turn update the module's buffer, leading to a fresh wave of rule activation. If multiple rules match the current state of the buffers, a selection process will pick one of them for execution. This is a stochastic process that takes into account previous experience.

Here is an example of a rule with one condition and two actions:

count {state start; from ?num1; to ?num2}

=> count {state counting},

increment {@module facts; @do get; number ?num1}

The condition matches the goal buffer, as this is the default if you omit the @module declaration to name the module. It matches a chunk of type count, with a state property whose value must be start. The chunk also needs to define the from and to properties. The condition binds their values to the variables ?num1 and ?num2 respectively. Variables allow you to copy information from rule conditions to rule actions.

The rule's first action updates the goal buffer so that the state property takes the value counting. This will allow us to trigger a second rule. The second action applies to the facts module, and initiates recall of a chunk of type increment with a property named number with the value given by the ?num1 variable as bound in the condition. The get operation directs the facts module to search its graph for a matching chunk and place it in the facts module buffer. This also is a stochastic process that selects from amongst the matching chunks according to statistical weights that indicate the chunk's utility based upon previous experience.

The above rule would work with chunks in the facts graph that indicate the successor to a given number:

increment {number 1 successor 2}

increment {number 2 successor 3}

increment {number 3 successor 4}

increment {number 4 successor 5}

increment {number 5 successor 6}

...

You can use a comma separated list of chunks for goals and for actions. Alternatively you can write out the chunks in full using their IDs and the @condition and @action properties in the rule chunk. The above rule could be written as follows:

count c1 {

state start

from ?num1

to ?num2

}

rule r1 {

@condition c1

@action a1, a2

}

count a1 {

state counting

}

increment a2 {

@module facts

@do get

number ?num1

}

Whilst normally, the condition property must match the buffered chunk property, sometimes you want a rule to apply only if the condition property doesn't match the buffered chunk property. For this you insert an exclamation mark (!) as a prefix to the condition's property value. You can further test that a property is undefined by using ! on its own in place of a value. In an action you can use ! on its own to set a property to be undefined.

In the following rule, the first condition checks that the from and to properties in the goal buffer are distinct.

# count up one at a time

count {@module goal; state counting; from ?num1; to !?num1},

increment {@module facts; number ?num1; successor ?num3}

=>

count {@module goal; @do update; from ?num3},

increment {@module facts; @do get; number ?num3},

console {@module output; @do log; value ?num3}

For properties whose values are names, numbers or booleans, the values can be matched directly. For ISO8601 dates, the value corresponds to an ID for the iso8601 date chunk, and hence date values are compared in the same way as for names. For values which are comma separated lists, the lists must be the same length and each of their items must match as above.

You can write rules that apply when an action such as retrieving a chunk from memory has failed. To do this place an exclamation mark before the chunk type of the condition chunk, e.g.

!present {@module facts; person Mary; room room1}

which will match the facts module buffer after a failure to get a chunk of type present with the corresponding properties. See below for details of response status codes.

When a condition has a property whose value is a list, the corresponding property value in the module buffer must be a list of the same length, and each item in the two lists must match. You can use ! before an item in the condition's list when you want to check that the buffer's list item isn't a particular value. You can use * for an item in the condition's list when you don't care about the corresponding value of the the buffer's list item.

Both conditions and actions can use @id to bind to a chunk ID.

Modules must support the following actions:

- @do clear to clear the module's buffer and pop the queue

- @do update to directly update the module's buffer

- @do queue to push a chunk to the queue for the module's buffer

- @do get to recall a chunk with matching type and properties

- @do put to save the buffer as a new chunk to the module's graph

- @do patch to use the buffer to patch a chunk in the module's graph

- @do delete to forget chunks with matching type and properties

- @do next to load the next matching chunk in an implementation dependent order

- @do properties to iterate over the set of properties in a buffer

- @for to iterate over the items in a comma separated list

Apart from clear, update and queue, all actions are asynchronous, and when complete set the buffer status to reflect their outcome. Rules can query the status using @status. The value can be pending, okay, forbidden, nomatch and failed. This is analogous to the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP) and allows rule engines to work with remote cognitive databases. To relate particular request and response pairs, use @tag in the action to pass an identifier to the subsequent asynchronous response where it can be accessed via @tag in a rule condition.

Actions can be used in combination with @id to specify the chunk ID, e.g. to get a chunk with a given ID. Additional operations are supported for operations over property values that are comma separated lists of items, see below. The default action is @do update. This updates the properties given in the action, leaving existing properties unchanged. You can use @do clear to clear all properties in the buffer.

Whilst @do update allows you to switch to a new goal, sometimes you want rules to propose multiple sub-goals. You can set a sub-goal using @do queue which pushes the chunk specified by an action to the queue for the module's buffer. You can use @priority to specify the priority as an integer in the range 1 to 10 with 10 the highest priority. The default priority is 5. The buffer is automatically cleared (@do clear) when none of the buffers matched in a rule have been updated by that rule. This pops the queue if it is not already empty.

Actions that directly update the buffer do so in the order that the action appears in the rule. In other words, if multiple actions update the same property, the property will have the value set by the last such action.

The @do get action copies the chunk into the buffer. Changing the values of properties in the buffer won't alter the graph until you use @do put or @do patch to save the buffer to the graph. Put creates a new chunk, or completely overwrites an existing one with the same ID as set with @id. Patch, by contrast will just overwrite the properties designated in the action.

Applications can define additional operations when initialising a module. This is used in the example demos, e.g. to allow rules to command a robot to move its arm, by passing it the desired position and direction of the robot's hand. Operations can be defined to allow messages to be spoken aloud or to support complex graph algorithms, e.g. for data analytics and machine learning. Applications cannot replace the built-in actions listed above.

NOTE: the goal buffer is automatically cleared after executing a rule's actions if those actions have not updated any of the buffers used in that rule's conditions. This avoids the rule being immediately reapplied, but doesn't preclude other kinds of looping behaviours. Future work will look at how to estimate the utility of individual rules via reinforcement learning, and how much time is anticipated to achieve certain tasks. This will be used to detect looping rulesets and to switch to other tasks.

You can iterate over chunks with a given type and properties with @do next in a rule action, which has the effect of loading the next matching chunk into the module's buffer in an implementation dependent sequence. To see how this works consider the following list of towns and the counties they are situated in:

town ascot {county berkshire}

town earley {county berkshire}

town newbury {county berkshire}

town newquay {county cornwall}

town truro {county cornwall}

town penzance {county cornwall}

town bath {county somerset}

town wells { county somerset}

town yeovil {county somerset}

We could list which towns are in Cornwall by setting a start goal to trigger the following ruleset:

start {}

=>

town {@module facts; @do next; county cornwall},

next {}

next {}, town {@module facts; @id ?town; @more true}

=>

console {@do log; message ?town},

town {@module facts; @do next}

next {}, town {@module facts; @id ?town; @more false}

=>

console {@do log; message ?town},

console {@do log; message "That's all!"},

town {@module facts; @do clear}

The start goal initiates an iteration on the facts module for chunks with type town and having cornwall for their county property. The goal buffer is then set to next. When the facts buffer is updated with the town chunk, the next rule fires. This invokes an external action to log the town, and instructs the facts module to load the next matching town chunk for the county of Cornwall, taking into account the current chunk in the facts module buffer. The @more property is set to true in the buffer if there is more to come, and false for the last chunk in the iteration.

A more complex example could be used to count chunks matching some given condition. For this you could keep track of the count in the goal buffer, and invoke a ruleset to increment it before continuing with the iteration. To do that you could save the ID of the last matching chunk in the goal and then cite it in the action chunk, e.g.

next {prev ?prev}

=>

town {@module facts; @do next; @id ?prev; county cornwall}

which instructs the facts module to set the buffer to the next town chunk where county is cornwall, following the chunk with the given ID.

Note if you add to, or remove matching chunks during an iteration, then you are not guaranteed to visit all matching chunks. A further consideration is that chunks are associated with statistical weights reflecting their expected utility based upon past experience. Chunks that are very rarely used may become inaccessible.

You can iterate over each of the properties in a buffer by using @do properties in an action for that buffer. The following example first sets the facts buffer to foo {a 1; c 2} and then initiates an iteration over all of the buffer's properties that don't begin with '@':

run {}

=>

foo {@module facts; a 1; c 2}, # set facts buffer to foo {a 1; c 2}

bar {@module facts; @do properties; step 8; @to goal} # launch iteration

# this rule is invoked with the name and value for each property

# note that 'step 8' is copied over from the initiating chunk

bar {step 8; name ?name; value ?value}

=>

console {@do log; message ?name, is, ?value},

bar {@do next} # to load the next instance from the iteration

Each property is mapped to a new chunk with the same type as the action (in this case bar). The action's properties are copied over (in this example step 8), and name and value properties are used to pass the property name and value respectively. The @more property is given the value true unless this is the final chunk in the iteration, in which case @more is given the value false. By default, the iteration is written to the same module's buffer as designated by the action that initiated it. However, you can designate a different module with the @to property. In the example, this is used to direct the iteration to the goal buffer. By setting additional properties in the initiating action, you can ensure that the rules used to process the property name and value are distinct from other such iterations.

You can iterate over the values in a comma separated list with the @for. This has the effect of loading the module's buffer with the first item in the list. You can optionally specify the index range with @from and @to, where the first item in the list has index 0, just like JavaScript.

# a chunk in the facts module

person {name Wendy; friends Michael, Suzy, Janet, John}

# after having recalled the person chunk, the

# following rule iterates over the friends

person {@module facts; friends ?friends}

=> item {@module goal; @for ?friends; @from 1; @to 2}

which will iterate over Suzy and Janet, updating the module buffer by setting properties for the item's value and its index, e.g.

item {value Suzy; @index 1; @more true}

The action's properties are copied over apart from those starting with an '@'. The item index in the list is copied into the chunk as @index. You can then use @do next in an action to load the next item into the buffer. The @more property is set to true in the buffer if there is more to come, and false for the last property in the iteration. Action chunks should use either @do or @for, but not both. Neither implies @do update.

You can append a value to a property using @push with the value, and @to with the name of the property, e.g.

person {name Wendy} => person {@push Emma; @to friends}

which will push Emma to the end of the list of friends in the goal buffer.

person {name Wendy} => person {@pop friends; @to ?friend}

will pop the last item in the list of friends to the variable ?friend.

Similarly you can prepend a value to a property using @unshift with the value, and @to with the name of the property, e.g.

person {name Wendy} => person {@unshift Emma; @to friends}

will push Emma to the start of the list of friends in the goal buffer.

person {name Wendy} => person {@shift friends; @to ?friend}

will pop the first item in the list of friends to the variable ?friend.

Note This uses the same rather confusing terminology as for JavaScript arrays. We could use append and prepend in place of push and unshift, but then what names should we use in place of pop and shift?

Further experience is needed before committing to further built-in capabilities.

Modules may provide support for more complex queries that are specified as chunks in the module's graph, and either apply an operation to matching chunks, or generate a result set of chunks in the graph and pass this to the module buffer for rules to iterate over. In this manner, chunk rules can have access to complex queries capable of set operations over many chunks, analogous to RDF's SPARQL query language. The specification of such a chunk query language is left to future work, and could build upon existing work on representing SPARQL queries directly in RDF.

A further opportunity would be to explore queries and rules where the conditions are expressed in terms of augmented transition networks (ATNs), which loosely speaking are analogous to RDF's SHACL graph constraint language. ATNs were developed in the 1970's for use with natural language and lend themselves to simple graphical representations. This has potential for rules that apply transformations to sets of sub-graphs rather than individual chunks, and could build upon existing work on the RDF shape rules language (SHRL).

Beliefs, stories, reported speech, examples in lessons, abductive reasoning and even search query patterns involve the use of statements about statements. How can these be expressed as chunks and what else is needed?

Here is an example from John Sowa's Architectures for Intelligent Systems:

Tom believes that Mary wants to marry a sailor

This involves talking about things that are only true in some specific context, as well as the means to refer to an unknown person who is a sailor. The latter can be easily handled given the determiner "a" which implies there is someone or something that has certain attributes, i.e. using a name as a variable for a quantifier. The former is a little harder, as we need a way to separate chunks according to the context, so that we don't confuse what's true in general from what's true in a given context.

One approach is use separate graphs for each context. This means that a cognitive module would have a set of graphs, and that we will need a means to refer to them individually. Another approach is to provide a way to indicate which context a given chunk belongs to, and to make the context part of the mechanism for retrieving and updating chunks. This would allow chunks for different contexts to be stored as part of the same graph.

The idea to be explored is to use @context as a property that names the context and to use this in rules as a basis for reasoning. In the above example, we need one variable for the sailor, and another pair of variables for the hypothetical situations implicit in the subordinate clauses.

Here is one possible way to represent the above example:

believes s1 {@subject tom; proposition s2}

wants s3 {@context s2; person mary; situation s4}

married-to s5 {@context s4; @subject mary; @object s6}

a s6 {@context s4; isa person; profession sailor}

This works with the existing rule language, provided that we assume a default context so that a @do get action without @context won't match a chunk in a named context other than the default context.

Contexts are also useful for episodic memory when you want to describe facts that are true in a given situation, e.g. when visiting restaurant for lunch, you sat by the window, you had soup for starters followed by mushroom risotto for the main course. A sequence of episodes can then be modelled as relationships between contexts.

If such contexts are widely used, then the implementation would benefit from a means to index by context for faster retrieval. This should be addressed when re-implementing the rule engine using a discrimination network for mapping module buffers to applicable rules.

In principle, contexts can be chained, e.g. to describe the beliefs of someone in a fictional story or movie, and to indicate when a context is part of several other contexts, i.e. forming a tree of contexts.

Note: when mapping chunks to RDF, contexts can be mapped to named graphs.

Tasks allow you to write rules that are only applicable to specific tasks. Tasks are associated with modules, and a given module can have multiple active tasks at the same time. You can use @task to name a task in a rule condition. This will succeed if the named task is currently active for the module for that condition. The set of active tasks are held independently of the module's buffer. Clearing the buffer doesn't clear the tasks. In rule actions you can use @enter with the name of a task to enter, and @leave with the name of a task to leave. You can enter or leave multiple tasks by using comma separated lists of task names.

Tasks and contexts are complementary. You use @context to name a particular event/situation, e.g. having dinner at a restaurant, and @task to segregate rules for different tasks within the overall plan for having dinner (finding a table, reviewing the menu, ordering, paying the bill).

It will often be convenient when leaving a task to automatically leave any of its sub-tasks. One idea would be to use @task to name a currently active task, and @subtask to enter a subtask for that task. If @task is missing, or doesn't name a currently active task, then @subtask would have the same semantics as @enter. We need to try this out to see how useful sub-tasks are in practice.

In any large knowledgebase we only want to recall what is relevant to the current situation based upon past experience.

- Our ability to recall information drops off over time unless boosted by repetition

- Closely spaced repetitions have less effect (the so called spacing effect)

- Spreading activation – concepts are easier to recall on account of their relationship with other concepts

This is modelled by using a chunk strength parameter which is boosted whenever a chunk is recalled or updated, and decays exponentially over time. This decay process only operates when the cognitive system is active. Spreading activation is modelled by a wave initiated when recalling or updating a chunk. The wave spreads through the chunk's properties to related chunks. The more such properties the weaker the wave energy given to each property. This energy boosts the chunk's strength as it passes them.

Chunk retrieval is stochastic with respect to chunk strengths, thus most of the time the strongest matching chunk is retrieved, but occasionally a weaker matching chunk will be returned instead. If two chunks have equal strengths they will have equal chances of being recalled.

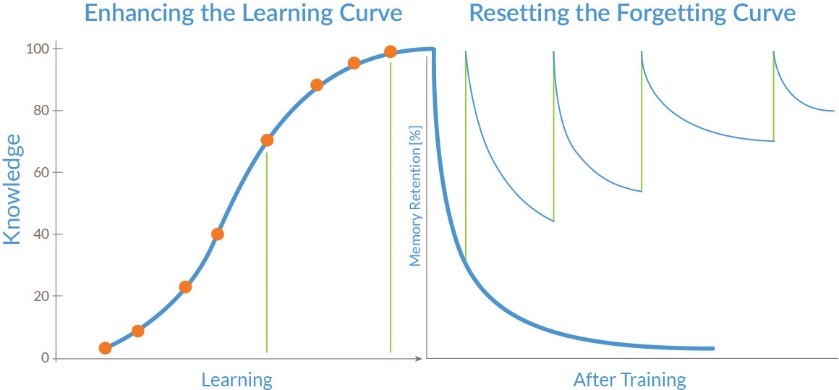

The above figure shows a sigmoidal curve for learning and exponential decay for forgetting. ACT-R uses a more complex model, and further exploration is needed to evaluate the trade off between the complexity of the model, the computational cost, and the effect on machine learning, see Said et al.

A starting point would be to model forgetting with a leaky capacitor, and learning as the injection of charge, where the amount of charge is smaller for short time intervals, but levels out as the interval increases. This can be modelled with the logistic function. For recall, we return the strongest matching chunk, subject to a minimum threshold, after multiplying the chunk strength by a random factor that is in the range 0 to ∞, and averages around 1. The factor is computed as ex where x is from a gaussian distribution centred on zero with a standard deviation of 0.2. The threshold ensures that recall will sometimes fail to return any chunks. This approach involves associating each chunk with a strength and a timestamp. Other ideas are welcomed!

The spacing effect describes the finding that long-term learning is more effective when learning events are spaced out in time, rather than presented in immediate succession. This also helps with the acquisition and generalisation of new concepts, perhaps because relevant features are reinforced whilst irrelevant features are more likely to be forgotten. An algorithmic approach to forgetting is thus related to the role of the brain as a prediction machine seeking order out of chaos.

- See: Distributing Learning Over Time: The Spacing Effect in Children’s Acquisition and Generalization of Science Concepts, Haley Vlach and Catherine Sandhofer

A web-based test suite for the major features of the chunks and rules format.

Forward chaining production rules involve testing the conditions for all of the rules against the current state of working memory. This gets increasingly expensive as the number of rules and the number of facts in working memory increases. It would be impractical to scale to really large memories with very large numbers of rules.

The brain solves this by first applying rules to a comparatively small number of chunk buffers, and second, by compiling rule conditions into a discrimination network (the Striatum) whose input is the chunk buffers, and whose output is the set of matching rules. This is followed by a second stage (the Pallidum) that selects which rule to use, and a third stage (the Thalamus) that applies that rule's actions. This approach was re-invented as the Rete algorithm by Charles Forgy, see below.

There are further opportunities for exploiting efficient graph algorithms such as Levinson and Ellis's solution for searching a lattice of graphs in logarithmic time, see John Sowa's summary of graph algorithms. A further consideration is how to support distributed graph algorithms across multiple cognitive modules that may be remote from one another. This relates to work by Sharon Thompson-Schill on a hub and spoke model for how the anterior temporal lobe integrates unimodal information from different cortical regions.

n.b. nature also invented the page rank algorithm as a basis for ranking memories for recall from the cortex based upon spreading activation from other memories.

This relates chunk rules to a few other rule languages:

A simpler version of chunks that restricts property values to names on the grounds of greater cognitive plausibility, see minimalist approach to chunks. It is an open question whether the minimalist approach will be better suited to machine learning of procedural knowledge.

OPS5 is a forward chaining rule language developed by Charles Forgy, using his Rete algorithm for efficient application of rules.

Here is an example:

(p find-colored-block

(goal ; If there is a goal

^status active ; which is active

^type find ; to find

^object block ; a block

^color <z>) ; of a cetain color

(block ; And there is a block

^color <z> ; of that color

^name <block>)

-->

(make result ; Then make an element

^pointer <block>) ; to point to the block

(modify 1 ; And change the goal

^status satisfied)) ; marking it satisfied

- See OPS5 User's Manual, Charles Forgy, 1981

Comment:

OPS5 marks goals as being active or satisfied, allowing multiple active goals at any one time. In chunks rules are triggered when they match the current state of the buffers. Chunks can be queued to the buffers for deferred processing when current thread of rule execution ends. The queue helps the cognitive system to avoid losing track when several things happen close together in time, e.g. two alerts from the sensory system. A more flexible approach is to keep explicit track of tasks in a graph, and reason about when and how to handle them.

Notation3 (N3) is a rule language for RDF that can be used to express rules based upon first order logic that operate over RDF triples. N3 supports quantifiers (@forAll and @forSome) and variables.

Here is an example involving cited graphs:

:John :says {:Kurt :knows :Albert.}.

{:Kurt :knows :Albert.} => {:Albert :knows :Kurt.}.

The first statement signifies that John says that Kurt knows Albert. The second statement is a rule that says that if Kurt knows Albert then we can infer that Albert knows Kurt. Whilst we know from the above that John says that Kurt knows Albert, we can't be sure of whether Kurt does in fact know Albert. We could add a rule to the effect that John only speaks the truth, e.g.

{:John :says ?x.} => ?x.

Here is an example that deduces if someone has an uncle:

{

?X hasParent ?P .

?P hasBrother ?B .

} => {

?X hasUncle ?B

}.

- Notation3 (N3): A readable RDF syntax 28 March 2011

- Notation3 as the Unifying Logic for the Semantic Web Dörthe Arndt's Ph.D thesis, 2019.

Comment:

One way to express first example in chunks as follows:

says {@subject John; @object s1}

knows s1 {@context c1; @subject Albert; @object Kurt}

which places what John says in a named context to keep what he says distinct from what is generally true.

The second example could be rewritten as an inference rule, e.g.

knows {@subject ?s; @object o} => knows {@subject o; @object s}

The third example involves the logical join of two facts and would be harder to express as chunk rules. One solution would involve iterating over the hasParent facts and then iterating over the corresponding hasBrother facts. This is where it would be easier to express the rule declaratively and invoke a graph algorithm to search over all matching facts, see more complex queries.